Nothing lasts forever. Like manufacturers of other mechanical devices, lock companies periodically update their products to be consistent with current technology. They do this to make better, safer, more reliable products, and also to remain competitive in the market place.

Sometimes these new, updated products are backwards-compatible with older models of the same brand, sometimes not. In the case of mortise locks I can say with some confidence, mostly not. One cannot replace a Schlage K series mortise lock body with an L series and expect the trim to work. The same is true of the newer Sargent 8200 vs. the older 8100 and the Yale 8800 series vs. the previous 8700 series. As these older locks age and must be replaced these differences can become a problem, since the existing trims and cylinders on site may not be usable with the new lock bodies. And there are still plenty of these older lock bodies out there. Case in point, although the Yale 8700 series was discontinued in 2006, one facility I know is filled to the brim with these mortise locks.

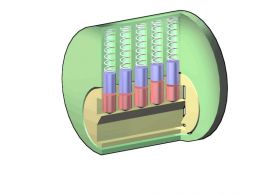

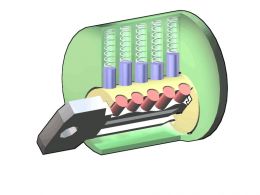

Although I foresaw that they would not be able to use the existing trims with their new locks I failed to anticipate that the existing cylinders would also be incompatible. But they were and here is why. On the left the cam that works with the Yale 8700 is in the process of being removed from a Medeco small format interchangeable core (SFIC) housing. In the first picture below, the correct cam has been installed.

In the second picture you can see that the new cam is not only thinner than the old cam, it’s also slightly longer. There is no way that old cam is going to work. Luckily, on a Medeco SFIC housing the cams are interchangeable, unlike most others on which the cams are permanently attached.

Please visit my friends’ site:

http://www.americanlocksets.com/mortise-locks-c-38_159.html

Now I’m waiting to hear about the other SFIC housings on the job that have their cams staked on. But one cluster at time, eh?