A huge variety of door hinges are available in today’s commercial hardware market. Which hinge is right for your application? This article discusses hinge types, hinge characteristics, and basic guidelines

on how to choose a hinge for your application.

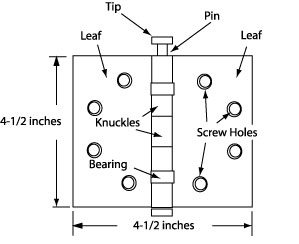

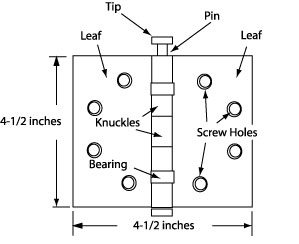

Parts of a Hinge

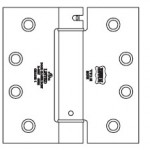

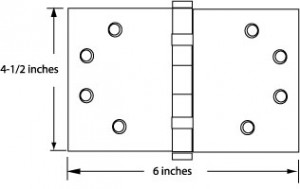

At right is an illustration that details the components of a full mortise hinge. Pictured is the most common hinge used in the United States, a five knuckle, full mortise ball bearing architectural grade template hinge, four-and-a-half by four-and-a-half inches.

- The leaves are fastened to the door and door frame.

- The bearings keep the hinge aligned help the hinge last longer by reducing wear

- The pin (shown slightly withdrawn from the knuckles as if being removed) holds the leaves together and provides the axis on which the door will turn

- The knuckle is a loop of metal through which the pin passes

- The top tip rests on the top knuckle of the hinge, stabilizing the pin; the bottom tip is attached to the bottom knuckle and helps keep the interior of the knuckles clean.

Some Variations

The leaves could be of equal widths, or unequal; the leaves could be “swaged”, meaning bent to compensate for a door with a beveled edge; the bearings could be ball bearings, concealed bearings, lube bearings, or “plain bearings”, indicating no bearings at all; the pin could be non-removable or fixed; there could be five knuckles, three knuckles, or in some cases, no knuckles; and hinge tips could be decorative or could serve a purpose, such as hospital tips, which are beveled to prevent things from getting caught on them.

Commercial architectural grade hinges could be standard weight or heavy weight; they could have square corners or round; and they could be “template” or “non-template” hinges, indicating whether its screw pattern matches architectural conventions so as to fit in standard hollow metal door preps or not.

Electrical options are also available, such as electric though wire, concealed magnetic contact, exposed electrical contact, and others.

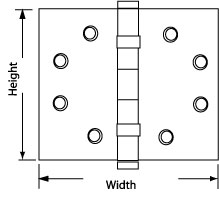

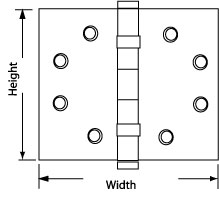

Hinge Sizing

To measure a full mortise hinge, also called a butt  hinge, lay it on a flat surface. Measure the height, then the width. When you specify full mortise hinge sizes, always refer to the height first, then the width.

hinge, lay it on a flat surface. Measure the height, then the width. When you specify full mortise hinge sizes, always refer to the height first, then the width.

Heavy Weight vs. Standard Weight Hinges

Heavy weight hinges are used for very heavy doors or doors that are subjected to very high traffic. Hinge “weight” actually refers to hinge leaf thickness. Heavy weight hinges leaves run closer to .200 gauge thickness, while standard weight hinges are more in the range .150 gauge thickness.

Hinge thickness is also dependent on hinge size. For example, a standard weight hinge 6 inches by 5 inches will be thicker than a standard weight hinge that is 4-1/2 by 4-1/2 inches.

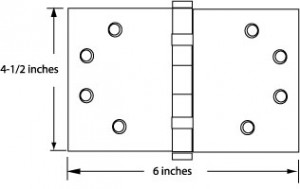

Wide Throw Hinges

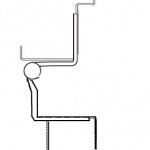

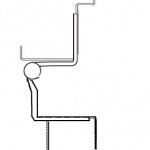

At right is shown a wide throw full mortise hinge. Wide throw hinges  enable a door to open 180 degrees when a decorative door molding might otherwise prevent it from doing so.

enable a door to open 180 degrees when a decorative door molding might otherwise prevent it from doing so.

Other Types of Hinges

All the hinges lifted below are available in standard weight and heavy weight versions for different commercial applications. Illustrations at right show various kinds of hinges.

Full Mortise Hinges

As I said earlier, full mortise hinges are by far the most common type of hinge. They come in a wide variety to accommodate diverse applications.

Half Mortise Hinges

Half mortise hinges are hinges that have one leaf mounted to the visible  front of the frame and the other leaf mounted in a hinge prep, or mortise, on the edge of the door.

front of the frame and the other leaf mounted in a hinge prep, or mortise, on the edge of the door.

Half Surface Hinges

Half surface hinges are hinges that have one leaf mounted to the surface of the door and the other leaf mounted into a hinge prep on the jamb part of the door frame.

Full Surface Hinges

Full surface hinges have both leaves visible when the door is closed. One leaf is fastened to the surface of the frame and the other to the surface of the door.

leaf is fastened to the surface of the frame and the other to the surface of the door.

Swing Clear Hinges

Swing clear hinges are designed so that when the door is opened to 90 degrees, the door itself is completely out of the opening. For example, if you needed to move a cart through a door that was 35-1/2 inches wide through a 36inch wide door, unless the door was hung on swing clear hinges, you would have to be able to open the door 180degrees in order to get the cart through the opening.

All of the hinges above are available in swing clear versions.

Template and Non-Template Hinges

“Template” hinges are full hinges that have a standard screw pattern and sizing to fit into an ANSI standard hinge prep, usually on a hollow metal door and frame. Most architectural (commercial) grade hinges are template hinges. Most residential hinges are non-template hinges.

Radius Corners

Radius corner hinges are hinges with rounded corners. “Radius” refers to  the radius of the circle thatwould exist if the curve of the rounded corner were continued to form a circle.Architectural hinges are available with 1/4-inch radius corners whereas residential hinges are available in 1/4-inch radius and 5/8 inch radius corners.

the radius of the circle thatwould exist if the curve of the rounded corner were continued to form a circle.Architectural hinges are available with 1/4-inch radius corners whereas residential hinges are available in 1/4-inch radius and 5/8 inch radius corners.

Residential Hinges

Residential hinges are very similar to architectural hinges, but there are differences. As stated above, more often residential hinges are non-template hinges, but they are sized the same as architectural hinges. Residential hinges also more often have radius corners than architectural hinges and are usually made of thinner gauge metal. Often one will see an architectural grade hinge used on exterior doors and residential grade hinges used on doors within the dwelling.

Spring Hinges

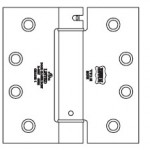

Spring hinges are architectural hinges that are spring loaded so as to shut the door. They are available in fullmortise, with or without radius  corner, in most sizes in which other full mortise hinges are made, and are available in template and non-template versions. A full mortise spring hinge is shown at right. Beneath the full mortise spring hinge is a picture of a double acting spring hinge for a door that swings both ways.

corner, in most sizes in which other full mortise hinges are made, and are available in template and non-template versions. A full mortise spring hinge is shown at right. Beneath the full mortise spring hinge is a picture of a double acting spring hinge for a door that swings both ways.

Continuous Hinges

Continuous hinges are hinges that extend the full height of the door. They are widely used on aluminum storefront and hollow metal applications. They are a good alternative for high traffic applications where added durability is necessary. Continuous hinges are available in aluminum, steel, or stainless steel, and, like architectural hinges, are available in different types to accommodate different conditions. Many of these configurations match those discussed in this article.

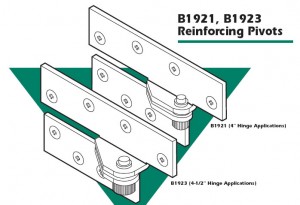

Pivot Hinges

Pivot hinges are used on heavy doors in high traffic applications and on many aluminum storefront doors. Since the weight of the door rests on the bottom pivot, the door does not “hang” as it does with other types of hinges, therefore there is less risk that the door will sag over time. At right is a picture of a pivot set from Rixson Hardware’s pivot catalog.

weight of the door rests on the bottom pivot, the door does not “hang” as it does with other types of hinges, therefore there is less risk that the door will sag over time. At right is a picture of a pivot set from Rixson Hardware’s pivot catalog.

Electrified Hinges

Full mortise, pivot, continuous hinges and others are available with electrical options such as:

- Electric Through Wire: a number of conductors are threaded through the hinge in order to conduct electricity from the door frame into the door (or vice versa) to power electric locks or transmit contact closure from monitor switches in the door or in the locking hardware. Available with anywhere from 2 to12 conductors, typically 24 gauge wire. 2conductor,18 gauge wire is also available.

- Concealed Magnetic Contact: a magnetic contact reed switch is concealed in the leaves of a full mortise hinge. When the door is opened, the leaves are spread apart, breaking or making the contact. HInges with concealed magnetic contact are handed.It is possible to have both the above options in the same hinge.

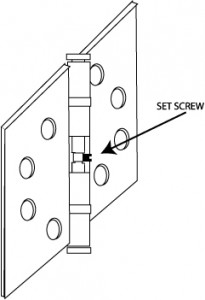

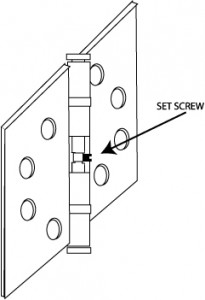

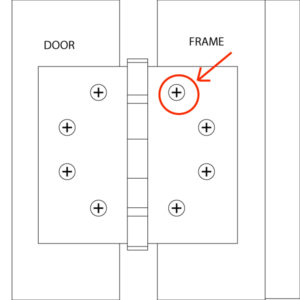

Non-Removable Pins

In situations where you have an out-swinging secured door, you can use hinges with non-removable hinge pins. Non-removable hinge pins are pins which have a groove milled in them in the middle. A set screw is threaded through the middle knuckle to mate with the groove (see picture at right) to inhibit burglars from pulling the pin and the door to gain entry. (In the picture, the center knuckle is not shown so that theset screw can be seen.)

Since the door was wood I could have pulled the door, removed the hinges, planed the hinge edge and re-cut the top and middle hinge mortises to bring the lock edge up and back in line with the frame; or I could broken into the walls on both sides and adjusted the door frame so it would be square again. But because I am old, tired, and was not getting paid I decided to take the easy way out: I shimmed the bottom hinge, forcing the lock side of the door slightly up so that the lock would once again align with the electric strike.

Since the door was wood I could have pulled the door, removed the hinges, planed the hinge edge and re-cut the top and middle hinge mortises to bring the lock edge up and back in line with the frame; or I could broken into the walls on both sides and adjusted the door frame so it would be square again. But because I am old, tired, and was not getting paid I decided to take the easy way out: I shimmed the bottom hinge, forcing the lock side of the door slightly up so that the lock would once again align with the electric strike.

weight of the door rests on the bottom pivot, the door does not “hang” as it does with other types of hinges, therefore there is less risk that the door will sag over time. At right is a picture of a pivot set from Rixson Hardware’s pivot catalog.

weight of the door rests on the bottom pivot, the door does not “hang” as it does with other types of hinges, therefore there is less risk that the door will sag over time. At right is a picture of a pivot set from Rixson Hardware’s pivot catalog.