There are many ways to lock a door electrically. Here are a few of the most popular:

- Electric Strike

- Electromagnetic Lock

- Electrified lock

- Electric Latch Retraction exit device

Voltage and Current

Two main factors are universal in choosing a power supply, but some kinds of electric locking devices require special considerations. The first universal consideration is the voltage required by your electric devices. The second is the amount of current drawn by these devices.

As of this writing, most strikes, magnets and locks are field selectable for a variety of voltages, mostly 12 or 24 VDC. Some are not field selectable. Almost all electric latch retraction exit devices are 24 VDC. The important factor is, what voltage will be used to power the devices. Voltage is important (aside from the fact that running an electric device on the wrong voltage may cause a fire) because voltage affects current draw. Current draw (measured in Amperes, or ‘Amps’) determines the need for power supply capacity.

Following are examples of how the voltage affects current draw:

HES 1500 series electric strike:

- .24 Amps @ 12 VDC

- .12 Amps @ 24 VDC

Schlage Electronics M490 electromagnetic lock:

- .65A @ 12 VDC

- .35A @ 24 VDC

SDC 7800 series electrified mortise lock:

- 600 mA @ 12VDC

- 300 mA @ 24VDC

Yes, there is a trend here. 12VDC draws twice as much current as 24VDC. Good to know. A little clarification may be in order:

.24 Amps = 240 mA

Now that we have that cleared up, let’s say that we have a six-door access control project and we’re using 24VDC. On four of the doors we’ll use the HES 1500; on one door we’ll use the M490 mag and on the last door we’ll use the SDC 7800 electrified mortise lock.

Just for variety, let’s add a Sargent 80 series exit device with motorized latch retraction:

- 1 amp @ 24VDC

The arithmetic looks like this:

.12 + .12 + .12 + .12 + .35 + .30 + 1 = 2.13 Amps total current draw

You want to allow at least a 25% cushion so that the power supply does not have to work too hard. Therefore, rounding up, a 3-Amp power supply would be a safe bet.

Distance of Wire Run

The distance between the power supply and the appliance to be powered is also an important factor. It may determine how many power supplies you need.

Using an online voltage drop calculator I was able to determine that a 1,000-foot wire run (one-way) using 18-gauge two-conductor wire, with a current draw of 120 mA, the voltage drop will be less than 1 percent. With a 1-Amp current draw, and all other parameters the same, the voltage drop would be about 27 percent. Therefore, whereas the 1,000-foot wire run would not be a factor to run one HES 1500 strike a 120 mA, it would be a factor in powering the Sargent exit device with electric latch retraction at 1 Amp at that distance. This might mean that a separate power supply would be installed much closer to the Sargent and another power supply could power all the other devices.

Voltage drop can be managed to a degree by increasing the gauge of the wire. Using the Sargent electric latch retraction example, this time using 12-gauge wire instead of 18-gauge wire, voltage drop on a 1,000-foot one-way wire run would be 14 percent instead of 27 percent. Using thicker wire combined with moving the power supply closer to the device can mean the difference between a system that works well for years and one that soon fails.

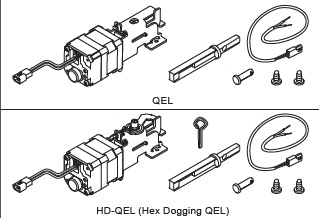

Electric Latch Retraction Exit Devices

In many cases the industry has shifted away from solenoid-driven electric latch retraction exit devices and moving more and more toward motor-driven latch retraction. Nevertheless, those solenoid-driven devices are still out there and many are still being sold. From a power supply point of view, it is very important to understand the difference.

When solenoids are activated, the draw an “inrush” of high current for a fraction of a second. For example, a Von Duprin EL99 rim exit device draws 15 Amps at 24 VDC for one third of a second, requiring it to have a special power supply. Their power supply for this application is the PS914-2RS, which will power up to two EL devices. What makes the power supply special is (1) the circuit board equipped with capacitors that gather the current and release it when it’s big enough to do the job and (2) a delay timer that allows the power supply to power up two devices one at a time, one-third of a second apart.

There are other power supplies that will work in this application: the Altronix STRIKEIT series power supplies, or the Command Access PS220 with PM300 power booster are two such. Each will power up to two solenoid driven electric latch retraction exit devices.

As shown earlier in this article, motorized latch retraction exit devices also draw more current than other kinds of electric locking devices. However, they draw much less current than solenoid driven latch retraction exit devices. Most manufacturers say to allow 1 amp per device. Check the install instructions for your particular device to be sure.

Options

Following are some accessories you can add to make your power supply easier to install and/or service, or to add functionality.

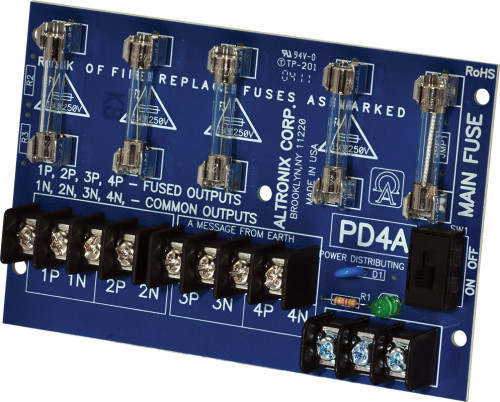

Power Distribution Board

If you have a power supply with one or two sets of outputs and need more outputs, you can add a power distribution board. The power distribution board distributes power evenly among several sets of output contacts. This can come in handy when troubleshooting a power supply that is powering multiple devices.

Relay Board

Relays are electrically operated switches. You flick the lights on in your room with your finger. Instead of a finger, the relay uses electricity. Relays typically draw a very small amount of electrical current. This can be useful in a variety of applications.

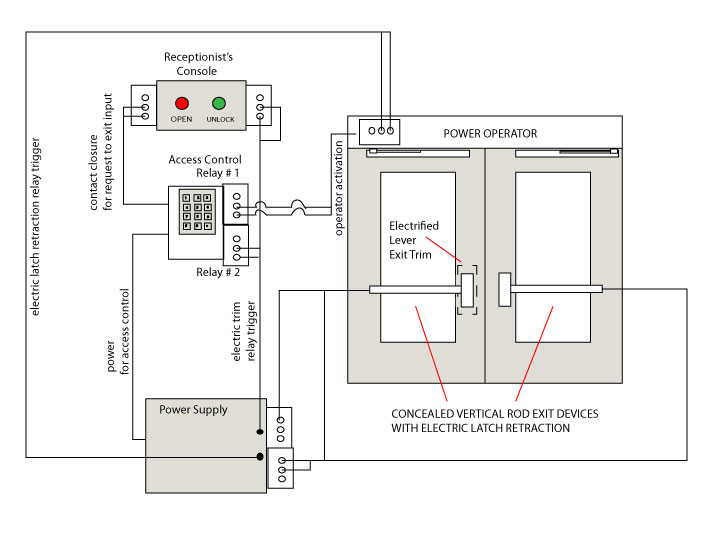

One example is in a simple access control system, where a receptionist pushes a button to activate an exit device with electric latch retraction that draws 1 Amp, 150 feet away. Instead of of running 1-Amp current from the power supply to the pushbutton, from the pushbutton to the device, and from the device back to the power supply, use the pushbutton to trigger a relay in the power supply to power the device. Only the few milliamps needed to power the relay will run back to the pushbutton. This makes the system much safer for the receptionist and avoids any voltage drop problems from the extra wire run back to the pushbutton.

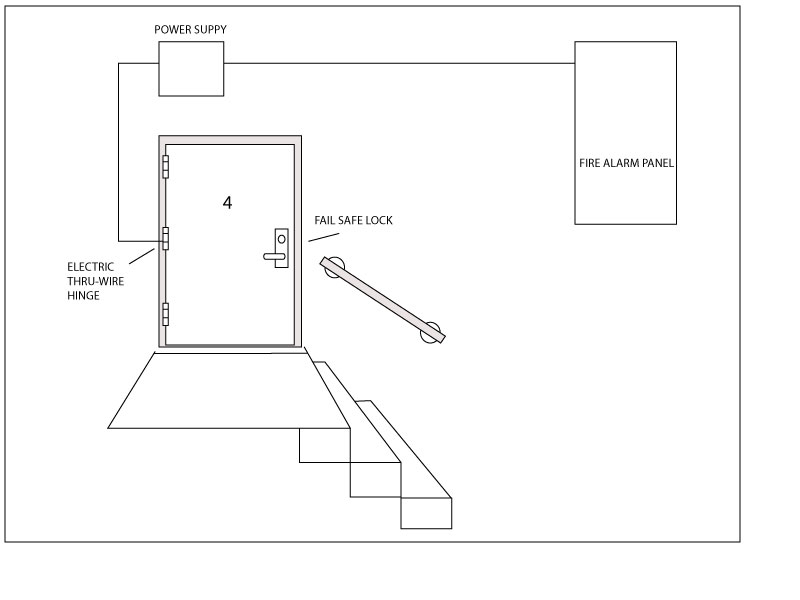

Fire Alarm Relay

The fire alarm relay option allows connection to the fire alarm panel, so that in the event of an alarm the panel can shut off the power supply.

Logic Board

Logic boards are boards with multiple relays and internal switches. These are used to perform more complex functions, such as activating electric latch retraction exit devices and then, a fraction of a second later, activating an automatic door opener.

Timers

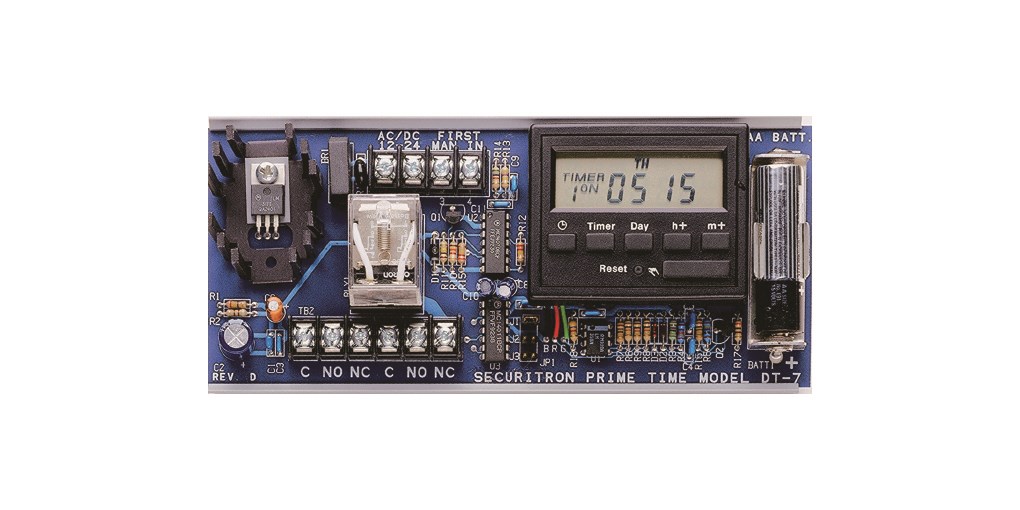

There are two main types of timers found in power supplies that are used with electric locking devices: 24-hour timers and delay timers.

24-hour timers are used to keep doors locked or unlocked for variable periods at specific times. Typically these timers can be programmed for a number of lock or unlock events. Simpler units might be used to unlock a door in the morning and then lock it back up at night every day. More versatile units can be programmed to behave differently on weekends and holidays.

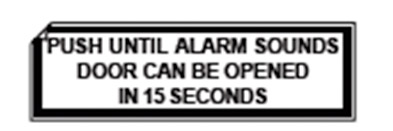

Delay timers are used to time the re-locking of the electric device after it has been activated. For example, the receptionist pushes the button at her desk and immediately lets go. The timer powers the electric strike for six or seconds to allow the visitor time to push the door open.